Camp Douglas, Chicago, Illinois

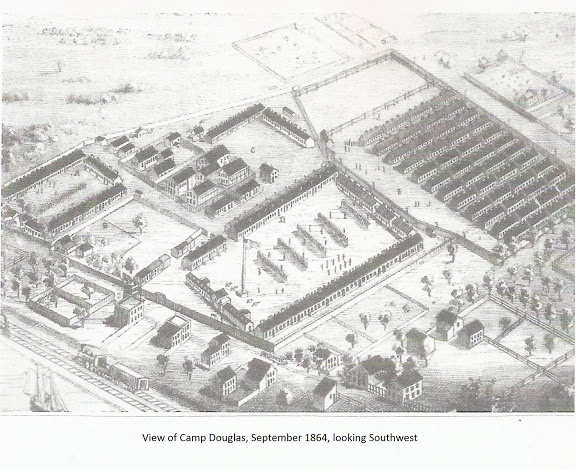

On April 15, 1861, Judge Allen C. Fuller, later Illinois Adjutant General, recommended the site for a reception and training camp for Northern District volunteers. The camp was hastily constructed and was in a constant state of flux throughout its history with most of the buildings being made of whitewashed wood unfinished on the inside. The only building built on a stone foundation was likely the camp headquarters building.

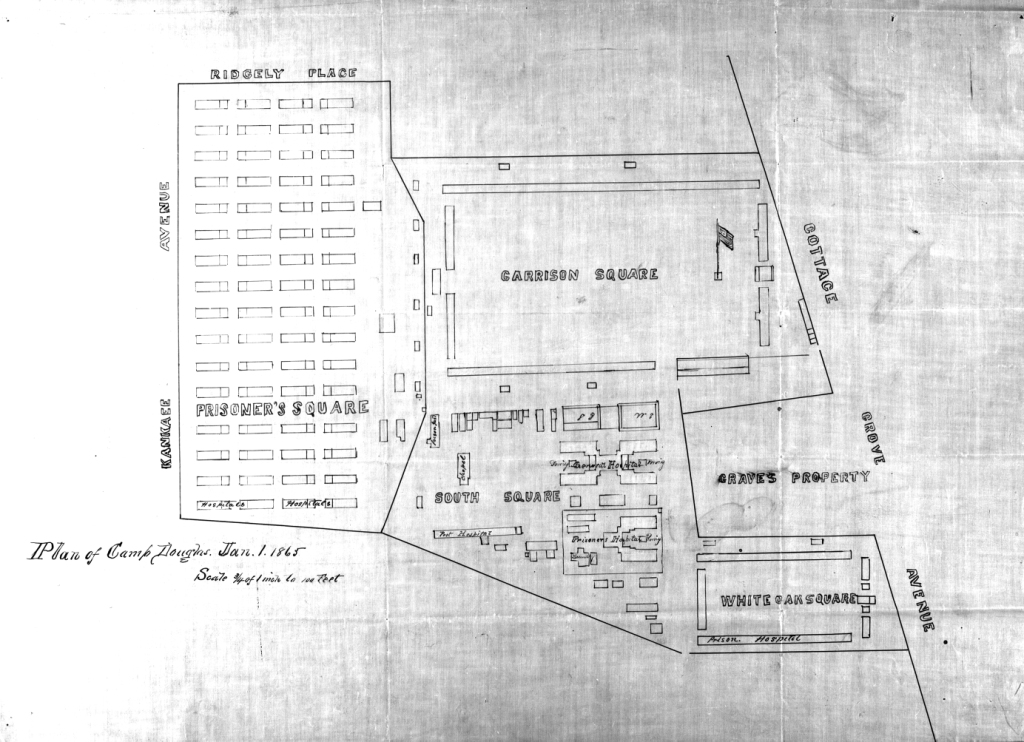

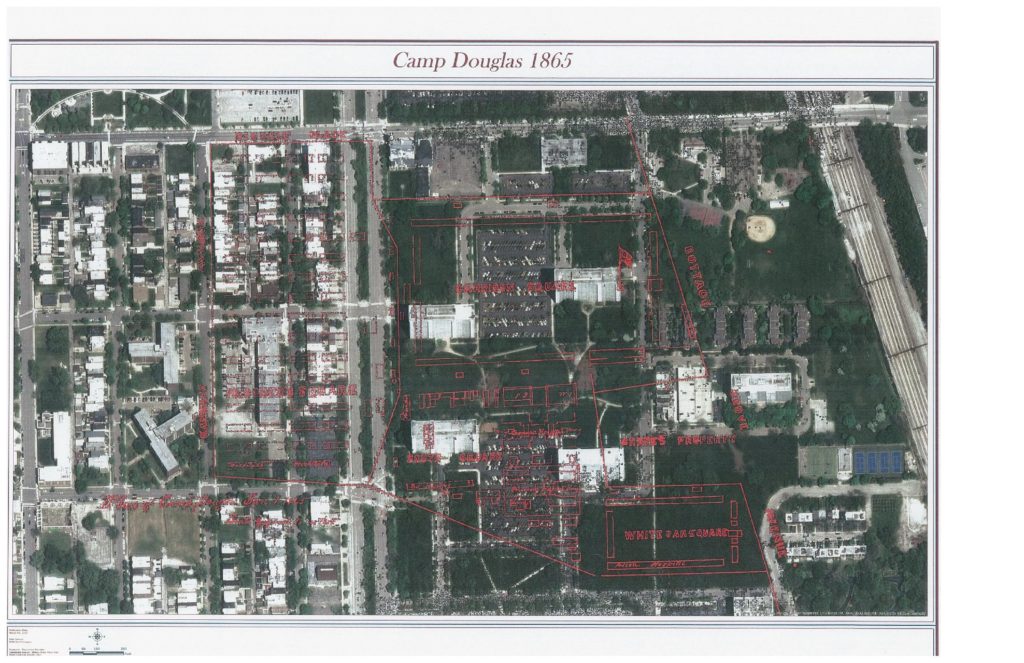

The Camp Ultimately Consisted of Four Parts

An area known as Garrison Square, to the north fronting on Cottage Grove, contained the main gate to the camp and the camp’s headquarters, an eighty by forty foot permanent building built on a stone foundation, and barracks for officers and men permanently assigned to the camp. The Square was approximately twenty acres in area. The barracks surrounded a large rectangular parade ground with the camp flagpole located west of the headquarters building. Stables were initially located at the southern end of Garrison Square. Other administrative buildings, including hospitals, quartermaster buildings, and a saw mill, were also located in Garrison Square. The original water hydrant was located in the northeast corner of the square and served as the sole source of clean water serving the entire camp. Over time, a total of three hydrants served the officers and men living in buildings on Garrison Square.

The ten acre White Oak Square, to the south fronting on Cottage Grove, contained one-story troop barracks. These barracks housed Confederate prisoners of war until early 1864, when Prisoners Square was opened. The privies, also referred to as sinks or latrines, were out back. In the early days of the camp, these latrines were simply shallow trenches.

South Square or Hospital Square was located on approximately ten acres west of White Oak Square along Thirty-Third Place. This contained the hospitals and various quartermaster and other support facilities.

Prisoners Square encompassed twenty acres located along the western side of the camp and ran from 31st to 33rd streets on Giles Avenue. Initially it contained barracks in a square configuration similar to Garrison Square. When the newly-constructed barracks opened in January 1864, there were 36 completed barracks of the total of 66 built by late 1864. A variety of administrative and logistical structures were also contained in Prisoners Square. These included a “sutler’s store” (providing comfort items to prisoners for credits available in exchange for cash), drug dispensary, surgeon’s office, photo studio, guard house, express office, and and wash houses, coal sheds, and nine hydrants.

History of Camp Douglas

More than 40,000 Union soldiers were received and trained at Camp Douglas during its existence. This number included African-American volunteers. The first troops were received in September 1861. Within a month there were nearly 5,000 men in camp. From the arrival of the first troops, Camp Douglas and its satellite camps acted as a reception and training center for the Northern District of Illinois. The state of Illinois had been divided into three military districts, with the Northern District consisting of the area from the southern boundary of Cook County to the Wisconsin state line, and Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River. Nearly two dozen infantry regiments, two cavalry regiments and a number of artillery units entered Union service at Camp Douglas.

Camp Douglas was one of only a few camps in the Union to receive African-American volunteers. In 1860 the African-American population of Illinois was 7,628, of which 3,809 were male, with 1,622 men of military age. Prior to 1863, approximately 700 Illinois African-Americans had joined the Union army in other states. The potential pool of soldiers was increased by nearly 22,000 escaped slaves from Missouri who moved to Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky between 1860 and 1862. The 29th U.S. Colored Infantry was the only African-American Regiment (approximately 1,000 men plus officers) recruited in Illinois. Recruiting began in November 1863. While the unit entered service in Quincy, Companies B and C (approximately 100 soldiers plus officers each) were recruited in Chicago. These soldiers were quartered at Camp Douglas until they were moved to Quincy. The 29th was commanded by John A. Bross, an attorney from Chicago. Colonel Bross had been Assistant U.S. Marshal and a U.S. Commissioner in Chicago. After the 29th was formed, replacement African-American soldiers from the Northern District were processed at Camp Douglas. The exact number of these recruits is unknown.

Near the end of 1861, it became apparent the Union Army required facilities to house Confederate prisoners who were not immediately paroled. Under the parole/exchange program agreed to by the Union and Confederacy, captured combatants agreed, in writing, not to participate in additional fighting until properly exchanged for soldiers from the opposing side.

Camp Douglas had major exchanges of prisoners in August 1862 and April 1863, that greatly reduced overpopulation of the camp. In August 1863, President Lincoln suspended the exchange of prisoners. The basis for the suspension was the position taken by the Confederate government that African-American soldiers would be treated as escaped slaves rather than prisoners of war. The suspension lasted until near the end of the war in 1865, when limited exchanges were authorized. This suspension of prisoner exchange had a significant impact on Camp Douglas that resulted in a growing population of prisoners and overcrowded conditions.

The United States Army set selection criteria for prisoner camps. These sites were to be first, a sufficient distance from the battlefields to preclude raids to release prisoners; second, a location with adequate transportation from the war, and finally, proximity to a metropolitan area that could provide logistic support to the facility. Chicago met all of these criteria, and Camp Douglas was selected as a major prison camp for Confederate prisoners of war in late 1861.

Early on, Major General Henry Halleck, Commander of the Department of Missouri, needed to find facilities for 12,000 to 15,000 Confederate prisoners from the surrender of Fort Donelson on February 16, 1862. The location of Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, northwest of Nashville within easy river transportation to Cairo, Illinois, made the movement of these first prisoners via the Illinois Central Railroad to Camp Douglas logical.

Colonel Joseph Tucker of the Illinois State Militia was responsible for building Camp Douglas and acted as its first commander. Even though Colonel Tucker reported to General Halleck that Chicago could hold 8,000 or 9,000 prisoners, the city and the military were not certain the camp could accommodate the prisoners. The first 1,258 prisoners arrived at Camp Douglas on February 20, 1862. Prisoners were assigned to barracks in White Oak Square that had just been vacated by Union troops.

The prison population grew to nearly 8,000 by the time of the first exchange of prisoners in September 1862. Only a handful of sick prisoners remained until additional prisoners began to arrive at year end. The peak of recruiting and receiving Union Regiments took place during the year. Satellite camps from Hyde Park to a mile or so north and west of the camp were busy with Union soldiers. These camps were frequently named for their commander or main supporter. Names included Camp Dunn, Camp Mulligan, Camp Seigel, Camp Webb, and others.

In July 1862, the Dix-Hill Cartel came into effect. This agreement between the Union and Confederacy stated, “All prisoners of war are to be discharged on parole in ten days after their capture.” This provision had a significant impact on the lack of willingness of the Union army to provide increased and improved facilities for Camp Douglas and other Union prison camps.

Throughout the war, the camp was almost continuously modified to adapt to its role as a prison. In June 1863, after the camp population was reduced to nearly zero by an exchange of prisoners, the camp was in deplorable shape. Damaged and burned buildings, deteriorating fences and an inadequate water and sewage system were clearly evident. The exchange in mid-1863, was the second major exchange. The first was in mid-1862. The United States Sanitary Commission recommended the camp be abandoned. Nonetheless, repairs were made and the camp continued as a major prison facility. In December 1863 camp commander Colonel Charles V. De Land ordered floors in prisoner barracks to be removed to prevent hiding prisoner-constructed tunnels and, later, barracks were raised about four feet to allow guards to see any activity under them.

The following table reflects the Prisoner population during the camp existence:

| Date | Beginning | Died, transferred, escaped, | Ending Prisoners |

| 1862 | |||

| March | 5,000 | ||

| July | 7,850 | 197 | 7,653 |

| September | 7,407 | 7,356 | 51 |

| 1863 | |||

| February | 3,884 | 444 | 3,440 |

| April | 380 | 41 | 339 |

| July | 49 | 2 | 31 |

| August | 3,203 | 7 | 3,196 |

| October | 6,115 | 142 | 5,973 |

| December | 5,874 | 213 | 5.661 |

| 1864 | |||

| February | 5,607 | 93 | 5,514 |

| April | 5,462 | 83 | 5,379 |

| July | 6,803 | 55 | 6,748 |

| October | 7,525 | 126 | 7,399 |

| December | 12,082 | 380 | 11,702 |

| 1865 | |||

| February | 11,239 | 1,973 | 9,266 |

| April | 7,168 | 1,060 | 6,108 |

| July | 30 | 30 | 0 |

Source: Eisendrath, Joseph L. Jr., “Chicago’s Camp Douglas, 1861-1865,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 53 no. 1 (Spring 1960): 37-63 compiled from OR Ser. II Vol VIII 986.

In September 1862, paroled Union forces captured at Harpers Ferry, Virginia were sent to Camp Douglas to serve out their parole until exchanged. These troops included approximately 8,000 paroled soldiers from the 60th Ohio, 32d Ohio, 65th Illinois (commanded by Colonel Daniel Cameron), 31st, 111th, 115th, 125th, 126th New York, and the 9th Vermont as well as artillery units from the 1st Independent Indiana Battery, 15th Indiana Battery, 19th Ohio Battery, 5th New York Battery and Phillips Chicago Battery. Of the 8,000, approximately 1,000 were from Illinois. These soldiers remained at Camp Douglas until December 1862 when they were exchanged. The exchange was purely administrative. The way it worked was that the Union parolees at Camp Douglas could return to active service when the Confederate government and union government determined that like number of rebel troops were on parole. All too often, however, rebel soldiers who were captured and released on parole never waited for the paper exchange to take place and immediately returned to combat. This use of the camp as a reception center for newly recruited soldiers, and a holding center for Union parolees, and Confederate prisoners of war severely taxed the facilities and managers of the camp. Some assistance came from Chicago citizens who rallied support for Union soldiers as well as the Confederates prisoners. Individual efforts as well as religious organizations, and the Sanitary Commission provided ongoing support to Camp Douglas throughout the war.

From the time of the arrival of the first Confederate prisoners, Chicagoans were curious to see their enemies and former countrymen. Near the Camp Douglas main gate on Cottage Grove, was a privately owned tower that was fifty feet high, and painted red, white, and blue. For five cents, anyone could climb the tower and observe the prisoners. There was a second tower providing viewing of Camp Douglas, a twenty-foot free observatory, built on the roof of the Cottage Grove Hotel.

Camp Douglas experienced a frequent change in its commandant and a recurring series of infrastructure problems. Hydrants that provided drinking water occasionally broke down, corrupt government contractors cheated on food rations, and the cheaply constructed barracks frequently needed repair. By October 1863, Colonel DeLand (Camp commander from August to December 1863) was spending considerable time and effort, mostly with prisoner help, improving the barracks and installing a new water and sewage system.

In December, he was replaced by General William Orme. During General Orme’s tenure in command, the high points were the development of a remodeled and modernized Prisoners Square to include plans for new barracks, a lighted stockade fence, and new latrines.

Colonel Benjamin J. Sweet was named commander of the camp on May 2, 1864 and would remain commander of Camp Douglas until nearly all Confederate prisoners were released in 1865. He infamously gave his guards the order “shoot to kill” any prisoner crossing the dead-line and incorporated a variety of corporal punishments for those who broke camp rules. Sweet introduced the “Morgan’s Mule” to the camp. This carpenter’s sawhorse was nearly fourteen feet tall and could accommodate several soldiers. Prisoners were forced to straddle the mule for several hours. While the device was notorious at Camp Douglas, similar horses were used throughout the Union army for prisoners and Union soldiers alike.

Colonel Sweet’s discipline included insistence on cleanliness of the prison area and the prisoners. Daily sweeping of barracks and weekly scrubbing were required. Prisoners were not permitted to empty dirty water in the streets and were expected to wash themselves and their clothing every Friday. Failure to meet these requirements resulted in a two-hour ride on the mule. While these measures seemed harsh to the prisoners, they resulted in the overall improvement of sanitary conditions in the camp and, undoubtedly, reduced disease and mortality.

Sweet was faced with circumstances that no other commander had faced. With the suspension of prison exchange in mid-1863 and the realization by the prisoners that exchange was not likely, Sweet was faced with elevated prisoner discontent, more escape attempts, and a growing prisoner population. A facility rated for 11,000 prisoners, peaked at 12,092 in December 1864. With the increase in prisoners and the unlikelihood of reduction through exchange, Colonel Sweet had to place a priority on completing the construction of barracks in Prisoners Square as well as other facilities for the prisoners. Work on Prisoners Square, done mostly by prisoners, continued through 1864, including the addition of a six inch water line to replace the one of three inches. Overall, the physical condition in the camp improved as Prisoners Square was expanded. Inspection reports in August, September and November 1864 indicated overall satisfactory condition of the prison facilities and the prisoners. These same reports showed concern for security and recommended additional guards and the issue of two cannons to control prisoners.

While inspection reports were improving, the health of prisoners was deteriorating. Smallpox was, in mid-to late 1864, of epidemic proportions. Lieutenant Briggs’ inspection report of September 4, 1864 stated, “The hospital for prisoners of war is not large enough. There are at least 200 prisoners sick in quarters that should be in hospital.”

Beginning in the summer of 1864 until the end of the year, Colonel Sweet was preoccupied by the grand Conspiracy of 1864. This was an attempt by Confederate agents, aided by opponents to the Lincoln Administration, to attack the camp from the outside and liberate the incarcerated Confederates. The scheme was fortuitously broken up by U.S. Secret Service agents; nonetheless its existence necessitated Colonel Sweet to continue to manage the camp with an iron hand. Finally on May 8, 1865, he received the long-awaited order from Colonel Hoffman ordering, “all prisoners of war, except officers above the rank of colonel, who before the capture of Richmond signified their desire to take the oath of allegiance to the United States and their unwillingness to be exchanged be forthwith released upon their taking the said oath, and transportation furnished them to their respective homes.” Those not taking the oath, ultimately, were released and provided no assistance in returning home. After the war, the government quickly sold off or destroyed the camp buildings, and the open area where prisoners once were kept became one the city’s first baseball fields.

Camp Douglas has the unenviable distinction of having the greatest number of deaths of any Union prison. The total death toll at Camp Douglas is somewhere between 4,243 (names contained on the monument at the Confederate Mound in Oak Woods Cemetery) and 7,000 (the extreme reported by some historians). Best estimates place the total at between 5,000 and 6,000. The exact number has never been established thanks to poor record keeping by both the Union and Confederate armies, and the actions of those who cared for the bodies after death. Initially, Confederate prisoners who died at Camp Douglas were buried in City Cemetery, soon to become Lincoln Park. In January 1867, the army agreed to remove remains from the City Cemetery, as well as from 655 bodies from graves at the smallpox cemetery near the camp, to Oak Woods Cemetery (67th Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, Chicago).

Even with the poor record keeping, it is acknowledged that more Confederate soldiers are buried in Chicago than anywhere north of the Mason-Dixon Line. The Confederate Mound at Oak Woods is also acknowledged as the largest mass grave in the Western Hemisphere.